I’ve now got a new Druidry video series started up on my YouTube channel. I hope that you like it! We start with Samhain…

Learning Druidry

Walking with the Ancestors

New video now up on my YouTube channel!

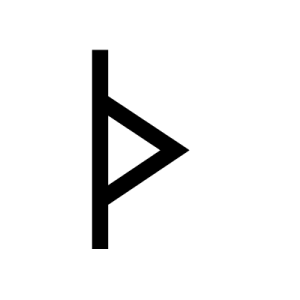

The Runes: Thorn

In this blog series, we will go through the runes as they are recorded in the Anglo-Saxon or Old English Rune Poem.

The third rune, Thorn is a tricky one, as its meaning has shifted with the Anglo-Saxon language. In Old Norse, it is connected to thurs, a malevolent entity of raw power. Some accord this entity to the giants found in Old Norse literature. But in Anglo-Saxon, it is thought that the shape of the rune dictated the meaning, and so we have “thorn”.[1] It is believed that the change occurred during the Christian period, and so the younger Norwegian Rune Poem may hold an older vestige of this rune’s meaning.

Alaric Albertsson states that the rune means “hawthorn”.[2] This may be due to the laying of hawthorn hedges in the Anglo-Saxon agricultural world, and taking rest in their shade, albeit carefully. It may connect to the English thyrses in this way (Old Norse thurses) in that the hawthorn, being a tree of liminality especially in Celtic lore (a faery tree) allows beings to travel between the worlds and thus, assail humanity should they so wish. As far as I can tell from my research, this is, however, all conjecture.

Swain Wodening makes the connection between Thorn and the Old Norse god Thor (Thunor in Anglo-Saxon). He states that Thor had connections to many thorny plants such as nettle and thistle, plants which use thorns or spikes to defend themselves, much as Thor was the defender of humanity against the giants.[3] All in all, these are all theories, and you will have to make your own mind up regarding the various possible meanings that surround this rune.

In the Anglo-Saxon or Old English Rune Poem, the verse reads:

Thorn is painfully sharp to any warrior

seizing it is bad, excessively severe

for any person who lays among them.

Thorn relating to a warrior is interesting, in that when I first read this verse, the concept of the Celtic Fianna warriors running through the woods with braided hair as a test came to mind. Should any of their braids catch on branches or thorns as they raced through the forest, they failed their test. Though this is a purely Celtic concept, there are similarities between Celtic and Northern European cultures in aspects of spirituality, artwork, commerce and more. Though this may have nothing to do with the Fianna warriors, it may have something to do with being out in the wildness of nature as a warrior, otherwise why mention it in relation to the flora? This could just be a mix of metaphors from the Old Norse into Anglo-Saxon, where a warrior fought off thyrses or giants, rather than was overly wary of the surrounding plant life. Or maybe it was a caution against the abundance of nettles that can be found all across the UK!

I found out the hard way when I first moved to these lands of the power of nettle, after walking through a field thick with them, not knowing what they were, and coming away with stinging hands and legs. We didn’t have stinging nettles where I grew up in Canada. So, maybe this is a simple warning not to make your camp or sleep near nettles when you are doing your warrior thing!

Another thing that came to mind when I first read the Old English verse is the Christian clergy in the line “excessively severe for any person who lays among them”. Saint Benedict was said to have come across a blackbird (a bird of liminality and the Druids in Celtic lore) which stayed with him for a moment, close to hand, before flying off. After this, Benedict became overcome with carnal thoughts of a woman he had seen once, and in order to shake off these emotions, he threw himself into a patch of nettles and briars. This remedy was so successful, Saint Benedict claims he was never overcome with that sort of temptation again. Severe? Yes, indeed. Excessively severe? I would say so. So perhaps this rune has a relation to Saint Benedict, but perhaps from a more “moderate” Anglo-Saxon Christian viewpoint.

From my point of view, I view thorn as a cautionary tale, based on my own experience with plants here in the UK which was hard learned. There are many spiky and stingy plants around here, such as hawthorn and nettle, but also blackthorn. Blackthorn has the longest, most vicious spikes of them all, and has a tendency to break off into the skin and then go septic. Unwary foragers, farmers and even horses can fall foul of the blackthorn. An extra element of Christianity comes into play with this as well, for it is said that the crown of thorns that Jesus wore came from the blackthorn.[4]

Whether you’re a warrior or a farmer, a forager or a gardener, being around thorns reminds you of the power of nature. A small plant may cause you great discomfort, a lapse of mindfulness can cause you great injury. Thorn reminds us of this, in that we need to take care, that we need to be aware of our surroundings (and this may again relate to the Old Norse thurs). Thorns can be seen as aggressive when we are on the receiving end, but we must remember that thorns protect a plant. Therefore, Thorn can be used in regards to workings of protection, although some may use it in the form of a curse. It is a good warding rune, to keep people away from you and your possessions. But it must be worked with carefully, lest you feel its sharp sting!

You can easily form the rune with your hands, with your left hand being straight and your right hand forming the sideways “v” shape. You can also stand in trance posture with your right arm at your hip, making the shape of the rune (and also giving off a “go on if you think you’re hard enough vibe).

Thorn is an interesting rune, in that its history is murky and muddied from different cultures. Yet it shows a great merging of understanding that I think is at the heart of Anglo-Saxon culture and tradition. Learn what you can from those around you, from the land itself, and let that inform your life. Take it all in. Use what works. The Anglo-Saxons were practical folk.

And watch out for thorns.

[1] Pollington, S. Rudiments of Runelore, Anglo-Saxon Books, (2011), p.18

[2] Albertsson, A. Wyrdworking: The Path of a Saxon Sorcerer, Llewellyn, (2011), p.98

[3] Wodening, S. Hammer of the Gods: Anglo-Saxon Paganism in Modern Times, Angleseaxisce Ealdriht, (2003) p. 185

[4] Don, M. “What’s Your Poison? Backyard Troublmakers”, The Guardian : https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2003/mar/09/gardens accessed 23 Sept 2020

Happy Equinox!

As we stand at the turning point of the seasons, we welcome this balance point, knowing that tomorrow we will welcome the growing darkness even as we welcomed the light in the spring. For without night there is no day, without spring no summer, without death there is no life. We are all a part of this cycle of manifestation, growth, decay and rejuvenation.

New Video: The Importance of Daily Practice for Pagans

New Lammas/Lughnasadh video!

The Awen (Part Two)

This is a continuation from my previous post on the awen, which you can read HERE.

So where does the flowing inspiration of modern Druidry come from then? And what is the difference between awen and the energy that is in all life?

In Welsh, we can trace it back to the 19th century, where aw means flowing or fluidity, and wen is spirit, or a being. We can more easily trace the concept and word back to medieval texts retelling the tale of Ceridwen and Taliesin.

The goddess Ceridwen was brewing a special potion for her son, Afagddu, tended by Gwion Bach. Some of the brew bubbled over and three drops scalded Gwion as he stirred the pot, and he put his thumb into his mouth to ease the soreness, taking in the magic of the brew meant for Afagddu. Ceridwen was enraged, and chased him, eventually eating him and then giving birth to him again. After she gives birth to him, she sets him on a boat and he was discovered alive and well later, and renamed Taliesin for his radiant brow. He becomes the most famous Bard of Britain.

The awen can be seen as being achieved through a deep connection to every aspect of the land, in whatever shape or form. We can undergo a kind of initiation into the awen much as Gwion Bach did, through the goddess Ceridwen and her special brew. We can drink from the cauldron of inspiration, but with that comes great trials and tribulations that go hand in hand with awareness and enlightenment.

The awen is also related to water and rivers, and not just the liquid brewed in Ceridwen’s cauldron. In the medieval poem “Hostile Confederacy” from the Book of Taliesin, it states:

“The Awen I sing,

From the deep I bring it,

A river while it flows,

I know its extent;

I know when it disappears;

I know when it fills;

I know when it overflows;

I know when it shrinks;

I know what base

There is beneath the sea. [1]

The awen relates to water on so many levels. The flowing spirit of water and the flowing spirit of awen share many similarities. Both are fluid, able to be contained and yet have their own freedom in their inherent sense of being. They follow their own currents, and can be beneficial when used with respect. When we follow the currents of life, the inter-connectedness of all things, we share that flow of awen and then come to know the fathomless depths that it can bring.

We also have the shamanic diviners in the Welsh tradition known as Awenyddion. There is also awen involved in divination and the quest for relationship with the divine. The awen is a vast subject that requires much study, but more to the point is requires experience. We can research the similarities between awen and the Hindu aspects of shakti, for example, or the Dao in Chinese philosophy. But we must feel the awen with every atom of our being in order the truly understand it.

But what is the difference between awen and the energy of life, or the life force? I would say that awen is the thread that connects us to that life force. When we connect in good relationship to the world around us, those threads shimmer with awen, with inspiration. We know that we are a part of the web, wholly and utterly connected. When we feel that connection with other beings, soul to soul, and our sense of self lessens, we are inspired by that connection. We then think of ourselves less, and our perception opens out to a wider perspective on the world, one that is more inclusive rather than just our own self-centred point of view. We become a thread in the web.

Awen helps us to see beyond ourselves, and perhaps paradoxically to allow us to see ourselves in everything. The poet Amergin described this beautifully what is now known as the “Song of Amergin”. When we see that we are a part of a whole, then we are inspired. When we lessen the sense of self, we are able to perceive so much more. When we have expanded our worlds to include everything within it, we become the awen.

I am the wind on the sea;

I am the wave of the sea;

I am the bull of seven battles;

I am the eagle on the rock

I am a flash from the sun;

I am the most beautiful of plants;

I am a strong wild boar;

I am a salmon in the water;

I am a lake in the plain;

I am the word of knowledge;

I am the head of the spear in battle;

I am the god that puts fire in the head;

Who spreads light in the gathering on the hills?

Who can tell the ages of the moon?

Who can tell the place where the sun rests?”[2]

Many Druid rituals begin or end with singing or chanting the awen. When doing so, the word is stretched to three syllables, sounding like ah-oo-wen. It is a lovely sound, which opens up the heart and soul. Sung/chanted together, or in rounds, it simply flows, as its namesake determines. Our hearts can open if we let them when chanting or singing the awen.

Yet I am sure that the awen is different for each and every Druid. The connection, and the resulting expression of that connection, the Druid’s own creativity, can be so vast and diverse. It is what is so delicious about it; we inhale the awen and exhale our own creativity in song, in dance, in books, in protest marches. The possibilities are endless, as is the awen itself.

We are never born, and we can never die: we are simply manifest for a while in one form, and then we manifest again in another when the conditions are right. For me, this represents reincarnation, the nitty gritty basics of it and the science behind reincarnation. The threads that bind this together are the awen.

[1] Mary Jones, “The Hostile Confederacy” from the Book of Taliesin, The Celtic Literature Collective, accessed January 12, 2018. http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/t07.html

[2] Lady Gregory, The Essential Lady Gregory Collection, Google Books, accessed January 13, 2018. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fx0tOGYDZXQC&dq

(This blog post is an extract from my book, The Book of Hedge Druidry: A Complete Guide for the Solitary Seeker.)

The Awen (Part One)

The Awen

The awen symbol is based on an original design by the 18th-19th century Druid revivalist, Iolo Morganwg. It consists of three lines falling to the right, centre and left. Modern Druidry incorporates the original source point of three dots, which can either be seen as points of light or drops from the cauldron of the goddess Ceridwen. The awen symbol represents, among other things, the triple nature of the Druid path, incorporating the paths of Bard, Ovate and Druid. It is not an ancient symbol, but a modern Druid symbol, used widely by Druids the world over, regardless of their opinion on Iolo and his work.

The awen symbol is based on an original design by the 18th-19th century Druid revivalist, Iolo Morganwg. It consists of three lines falling to the right, centre and left. Modern Druidry incorporates the original source point of three dots, which can either be seen as points of light or drops from the cauldron of the goddess Ceridwen. The awen symbol represents, among other things, the triple nature of the Druid path, incorporating the paths of Bard, Ovate and Druid. It is not an ancient symbol, but a modern Druid symbol, used widely by Druids the world over, regardless of their opinion on Iolo and his work.

The first recorded reference to Awen occurs in Nennius’ Historia Brittonum, a Latin text of circa 796 CE. “Talhearn Tad Awen won renown in poetry” is where we first see the word, and it tells us that Talhearn is the ‘father of Awen” in this instance. Sadly, this source tells us nothing more about Talhearn as being the “father of awen”, but perhaps later research may discover more clues about this reference.

A common translation of the Welsh word awen is “flowing inspiration” or “flowing poetry/poetic insight”. Awake to our own energy, and stretching out towards the energy of nature around us, we begin to see just what is the awen. It is an opening of one’s self, of one’s spirit or soul, in order to truly and very deeply see and connect to all life around us. When we are open, we can receive that divine gift, the inspiration that flows, whether it is from deity, nature, or whatever it is that you choose to focus on.

For awen to exist, there must be relationship. We cannot be inspired unless we are open, and we cannot be open unless we have established a relationship, whether that is with the thunder, the blackbird or a god. It is cyclical in nature; we open and give of ourselves and in doing so we receive, and vice versa. Letting go, releasing into that flow of awen allows it to flow ever more freely, and we find ourselves inspired not only in fits and bursts of enlightenment or inspiration, but all the time, carrying that essence of connection and wonder with us at all times. There is, of course, a line to be drawn, for we can’t be off our heads in ecstatic relationship with everything all the time. As with all language, a literal translation can be far too limiting. It’s good to have a context and some sort of description to relate the concept, but when confined to literalism we get stuck and are unable to see the bigger picture. Awen does mean flowing inspiration, but what is inspiration?

A really good idea, a bolt from the blue is one interpretation. However, there are many others. Inspiration is not just something that happens to us. It is something that we can cultivate, in true relationship. We are not subject to the whims of inspiration, but rather can access that inspiration on a daily basis through deep relationship. Indeed, awen is all about relationship, more than it being “a really good idea”. When we literally translate awen into inspiration, we can lose that context of relationship. With good relationship, we will have good ideas.

When soul touches soul, there is an energy; a source of inspiration. When we are aware of our soul interacting with other souls, we can harness that inspiration and see it in everything that we do. It doesn’t just happen every now and then, like a bolt out of the blue, but rather is in everything that we do. It requires a willingness for deep relationship, and a desire to be mindful in all our relationships.

This may sound a lot like Eastern philosophy; being very mindful. Mindfulness has become a large part of many Eastern philosophies, but I am sure that it has been around as long as human self-awareness has been around. Indeed, it may have been a large part of ancient Druidry, now lost to the mists of time. Taking inspiration from Eastern traditions with regards to our way of thinking is not much different to reading the works of Nietzsche or Plato. There is no monopoly on wisdom.

Mindfulness relates to awen in that when we are aware of our relationship to the world, when we see how we fit in the world then we can work in harmony with the world. We become an integral and integrated part of an ecosystem, where we know that everything that we do matters to the system in its entirety. The discipline gained from such mindfulness as practiced in the Eastern traditions and philosophies can be a great teacher in expanding our minds and helping us to learn more about ourselves. That also goes for other religions and philosophies as well. I’m sure the ancient Druids, just as much as Modern Druids today, loved reading about world religions and discussing philosophy.

There is a lot of talk about cultural misappropriation, however, in modern Paganism and it’s something that needs to be carefully considered. We do have to be aware of when we are taking something from another culture without its proper context and permission. Nevertheless, with religions or traditions such as Buddhism, for example, the Buddha said that enlightenment was for anyone to achieve, available to all, regardless of where they came from, whatever their background. It’s why we see so many different forms of Buddha being represented in sculpture. We have fat Buddhas from China, giant slim standing Buddhas in India, reclining Buddhas in Burma, sitting Buddhas carved straight out of the rock temples in Sri Lanka, elegant bronze-plated Buddhas in Japan and so on. In each country the Buddha looks different, as Buddha is within each and every person as well as having been a person in his own right. There is even a female Buddha known as Tara in Vajrayana Buddhism.

You will find that Druidry has much in common with many other Earth-based religions the world over, as well as many philosophies, both ancient and modern. We can be inspired by these and let them help us to change our perception, our way of seeing the world, from a self-centred point of view to a more holistic worldview, from a less human-centred perspective to one that is more integrated. In that, we are living the awen.

Awen is that spark set off by interaction, by integration. We do not exist in a bubble. We are surrounded by the world at all times, by the seen and the unseen. When we live integrated, we see the meaning that each relationship has, and that inspires us to live our lives accordingly. That inspiration is the heart and soul of Druidry.

Inspiration: to inspire, from the Latin inspirare, the act of breathing.

Indeed, it has many connotations to the breath and breathing. Awen can connect us to the world through the very act of breathing. All living things breathe in some form on this planet. The human species shares this breath, breathing in the oxygen created on this planet and exhaling it into the twilight. The air that we breathe has been recycled by plants and creatures for billions of years. The breath is the gateway to the ancestors, and to a deep understanding of the nature of awen. Awen is also shared inspiration, for we share this planet with everything else on it. Everything that we do has an impact, every breath we take, every action that we make. Breath links us to everything else.

When we remember that deep connection to everything else, we cannot help but be inspired. And we hope to inspire in return, much as our own exhalation is valuable to trees and plants who take in the carbon dioxide, turning it to oxygen for our own breath. Inspiration and expiration, inhalation and exhalation are all words for the act of breathing. Remembering the shared breath of the world, we come home to ourselves and rediscover the wonder and awe of existence. Then, we are truly inspired.

More about the awen in Part Two, coming up…

(This blog post is an extract from my book, The Book of Hedge Druidry: A Complete Guide for the Solitary Seeker.)

Latest Podcast Episode!

Here in the final installment of my YouTube and podcast mini-series on the elements. I hope you enjoy it! To listen to all podcast episodes, please visit my Bandcamp Page.

Beltane Full Moon Ritual

Join me as I set up and perform my ritual for the Beltane full moon, 2020. 🙂